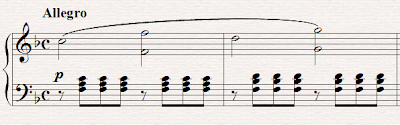

In the exposition, Beethoven presents a statement (forte). He then then answers the statement (piano) by sequencing it up a minor third. He repeats this process, then ends with a cadence on the dominant.

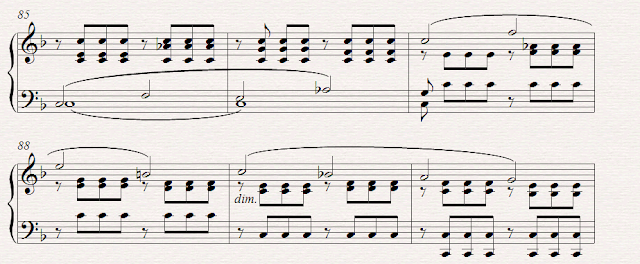

In the recapitulation, the statement and answer are switched. Originally, the first phrase was the statement; the second phrase was the answer. In the recapitulation, the first phrase overlaps with the flourish of the previous passage. So it is the second phrase that becomes the statement. To clarify this new function, Beethoven changes the dynamic to forte and drops the dotted-rhythm inner voice.

The third phrase, marked piano, becomes the new answer. But the melody is changed. The F-E-C that used to be the melody becomes an inner voice (presented in the dotted rhythm characteristic of the answer in the exposition). The new melody (B natural-C) anticipates the cadence and drives home the F major tonality. The statement and answer then repeat an octave higher, after which we have the cadence, marked sforzando. Note this procedure requires an additional measure. The passage is now seven measures long rather than the six measures we had in the exposition.

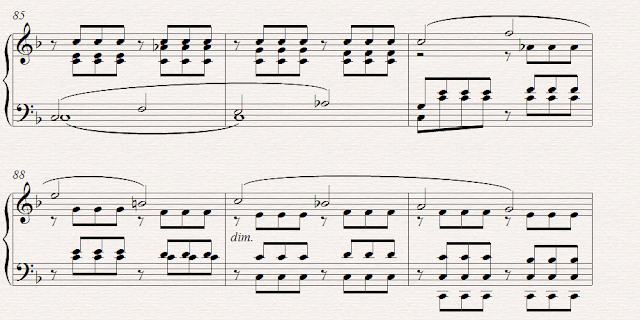

In the literal transcription below, I have followed Beethoven's procedure (from the exposition) of alternating the melody between the first and second violins.

In his arrangement, Beethoven makes some of the same decisions he made in the exposition. Specifically, (1) he replaces the alternating dynamics with sforzandi on beat three of each measure; (2) he incorporates the dotted quarter rhythm in all three upper parts at the cadence; and (3) he replaces the final chord with octave Cs (as I did in the transcription). We discussed these decisions when we examined measures 16 to 22. So we will restrict this discussion to decisions that are new in this passage.

One such decision is in the viola part. In the exposition, the viola alternated between doubling the first and second violin at the third or sixth. Here, the viola always doubles the second violin. This makes sense, since the second violin always has the more interesting part in this passage.

Beethoven chooses to omit the first violin altogether in the first measure. This thinning of texture offers a respite from the business of the preceding measures and supports the crescendo that begins in measure 109. When the first violin does enter, Beethoven changes the articulation, making the C a staccato quarter note rather than a half note. This makes the passage decidedly cleaner. As you can hear in the literal transcription, leaving these Cs as half notes weighs the passage down. (This isn't true on the piano because of the piano's faster decay.)

Even though the cello plays only repeated Cs, there are some changes to its part as well. For one, the sforzando is omitted in the first measure. Beethoven seems to be thinking of the inner voices as one unit and the outer voices as another unit. So he waits for the first violin to enter before the cello joins in the sforzandi.

Also, Beethoven changes the spot where the bass moves up an octave. In the piano version, this happens on beat three of measure 109. In the string version, it happens on the second eighth note of that measure (mimicking the similar move in the exposition). One could argue, however, that these spots are rhetorically identical. In each case, the octave leap occurs immediately after the phrase ends. But, because the last note of the phrase is a half note in the piano version and a staccato quarter note in the string version, the end of the phrase occurs in different places. In other words, the change in the cello part is simply a consequence of the change in the first violin part.

An interesting detail is Beethoven's treatment of the C on beat two of measure 107. In the piano version, this C ends the phrase from the previous measure. This phrasing made sense in the exposition, since this note was part of the motive. In this passage, however, it makes more sense to end the phrase on the E one beat earlier, at the end of the first violin's sixteenth-note flourish. In the string version, Beethoven does just that. The phrase ends on E, and the C becomes transitional, an anacrusis to the main motive. To make this clear, Beethoven gives the C to the second violin and makes it staccato.This is another example of Beethoven's paying more attention to voice leading in the string version than he did in the piano version.