In the late 18th century, the most common way for music-lovers to enjoy music was not to attend public concerts but to play it themselves. Amateur string quartets, for example. would often gather in members' homes to play through new pieces. And they did not restrict themselves to works originally written for string quartet. They also enjoyed playing arrangements of popular works of other genres. To accommodate this demand, publishers hired composers to make such arrangements

In 1801, in the wake of the popularity of Beethoven's opus 18 string quartets, Beethoven's publisher asked him to arrange some of his piano sonatas for string quartet. Beethoven began the project but stopped after only one arrangement, namely, of his Piano Sonata No. 9 in E Major. Perhaps he found the task to be too onerous, since he wasn't content merely to transcribe the sonata. He meticulously made changes to the music in order to render it more idiomatic for strings. He was quite happy with the end result, however. He bragged in a letter to his publisher that, aside from himself, only Haydn or Mozart could have managed it.

I thought it would be helpful for my own development as a composer to go through this arrangement in detail to see what changes Beethoven made. I could compare a literal transcription of the music with Beethoven's arrangement and ask myself why he made the changes that he did. If one wants to learn how to write a string quartet, what better teacher could one have than Beethoven himself? It would be nice to have my own personal ensemble to play through both versions for me so I could hear the differences. Unfortunately, I don't have that luxury. But I can come pretty close to reproducing that experience with Cubase and Sounds Online Symphonic Gold samples. Since this exploration might be of interest to other composers, I have decided to record it in this blog.

The first change Beethoven made was to raise the entire sonata a half step to the key of F Major. The reason for this change is obvious enough. All twelve open strings belong the key of F Major. Only three of the twelve belong to E Major. So double and triple stops will be easier in the new key. In addition, the transposition makes it easier to use the lowest register of the cello, since the low C string is now the dominant. In E Major, the lowest dominant available would be the B a seventh higher.

The first four measures of the piano sonata (transposed to F Major for easier comparison) are as follows:

A literal transcription (ignoring the pianistic doubling of the melody on the third beat of measures one and two) would be:

which would sound like this:

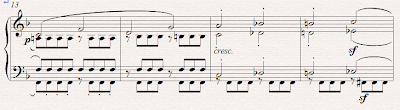

Beethoven, however, arranged these measures as follows:

which sounds like this:

Note Beethoven begins with a chord rather than with the unaccompanied C of the melody. This change has a practical benefit: It makes for easier ensemble playing if everyone starts together. But it also has an aesthetic benefit. As you can hear from listening to the samples, an unaccompanied C in the first violin sounds weak. The chord gives the opening more substance. This is unnecessary in the piano version, since the percussiveness of the piano lends sufficient weight to the unaccompanied C. To begin the movement with a fully voiced chord would sound cluttered on the piano. Beethoven does not, however, use the same chord on beat one as in the rest of the measure. He drops the bass down an octave and drops the middle voices down one chord tone. This keeps this opening chord distinct from the accompaniment that follows and maintains the effect of the opening rest in the piano version.

I was a little surprised to see that he did not change the spacing of the chords in the first two and a half measures (by raising the A and B-flat an octave, for example). In string writing, one does not generally have more space between the top two voices than between each of the bottom three. But Beethoven must have decided that to open the chord up would change the character of the theme. He waits until the last half of measure three to open the spacing, for reasons we will get to shortly.

Measure four presents a difficulty similar to that of the first beat of measure one. The final high F in the first violin would sound weak if it were articulated by itself over a sustained chord in the lower strings. Again, this is not a problem on the more percussive piano. To solve this difficulty, Beethoven has the bottom voices move rather than sustain a single chord. As in the first measure, he uses the low F in the cello, followed by an octave leap, to add weight to the first beat. He also adds a sforzando to the first beat in all four parts and leads into the sforzando with a crescendo in measure three, not indicated in the piano score. Finally, to help articulate the high F at the end of the phrase, he has the middle voices rise a chord tone on beat three, following the ascent of the melody.

To prepare for this new texture, Beethoven must re-voice the dominant chord at the end of measure three. He abandons the double stops in the second violin and raises the G an octave so that the voice-leading into the initial chord of the fourth measure sounds more natural.

We are only four measures into the sonata, and we can already see that this is no mere transcription as a lesser composer might have produced. Beethoven is taking great care to consider the differences between how the music sounds on a keyboard and how it will sound on strings.