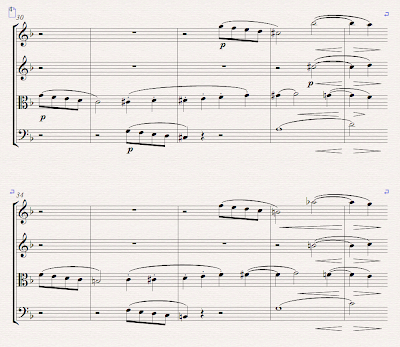

Here is what a literal transcription would sound like:

And here is Beethoven's arrangement:

In the piano version, Beethoven alternates between staccato and legato eighth notes in the left hand. In strings, this doesn't work. The legato eighth notes don't sound as energetic as they do on the more percussive piano. So the Beethoven makes all the eighth notes in the accompaniment staccato. In addition, he adds a staccato to the melody on the last note of each phrase. (Although this latter change is advisable in any event, given the first violin's ensuing drop.)

Beethoven also decides to score the two phrases differently. In the piano version, the phrases are identical except for the cadences. In the string version, he opts for a light, bouncy first phrase and a more dramatic second phrase. This is more typical of the Viennese style, so it is no surprise Beethoven chooses to do this. The real question is why he didn't do something similar in the piano version. Perhaps he thought such contrasts in texture are more important in string music than they are in keyboard music. Or perhaps this is simply another case of his changing his mind.

In the first phrase, Beethoven lightens the texture by raising the eighth notes in the bass an octave (giving them to the second violin) and by eliminating the alto line altogether. He also replaces some of the repeated notes in the cello with rests, specifically on beat three of measure 38 and on the weak beats of measure 41. And he replaces the cello's dotted half note at the end of the first phrase (on the downbeat of measure 42) with a quarter note. The viola pretty much stays out of the way. In the first two measures, it merely adds color by outlining the melody in staccato. In the next two measures, it is silent. All in all, these changes produces a lighter, cleaner sound than we hear in the transcription.

One effect of switching the bass and tenor lines is that it changes the way the phrase is harmonized, as the analysis above shows. We now have root position tonic chords in measures 39 and 40 rather than first inversion tonic chords. This is unusual. One generally shies away from root position tonic chords in the middle of a phrase, especially if that phrase is going to end with an authentic cadence, since they will weaken the cadence's effect. Beethoven solves that problem by tossing in a retardation at the end of the phrase. On the downbeat of measure 42, the second violin arpeggiates a dominant chord over the C in the bass, delaying the tonic until beat three. This is a nice attention to detail. The retardation isn't necessary in the piano version. But here the phrase would sound too static without it.

The descending arpeggio is a new motive, not present in the original. And Beethoven immediately exploits it. In the second half of measure 42, he repeats the motive in orchestral unison to transport the accompaniment down into the second octave.

In the second phrase, Beethoven eliminates the sustained notes in the accompaniment. Both the bass and tenor play the staccato eighth-note figure while the second violin doubles the first violin an octave below.

To construct the eighth-note pattern for the bass, Beethoven alternates the original bass note with the root or fifth of the chord. In the second half of the phrase, however, Beethoven makes some additional changes. Had he followed the same pattern, the end of the phrase would be as follows:

The first problem with this version is the preponderance of fifths and octaves at the end of the first measure. Beethoven solves this problem by breaking the pattern, having the bass move in thirds with the tenor:

A second problem is the poor voice leading in the tenor. Essentially, we hear alternating notes of the viola as outlining two separate parts. If we write out these two parts, we can see the voice-leading problems more clearly.

The B-flat at the end of the first measure wants to resolve to an A. Instead, it leaps upward to a D while the lower voice moves to an A. Similarly, the F at the end of the phrase wants to resolve to an E. So Beethoven raises the last beat of the first measure up an octave and has the line descend. Each dissonance now resolves naturally: