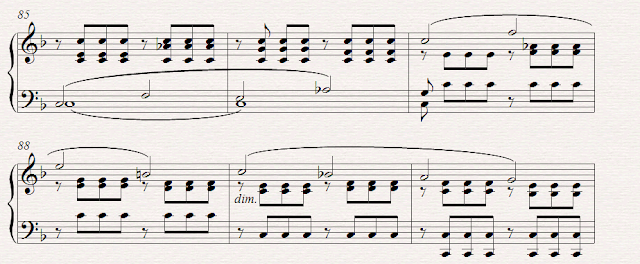

In the piano version, the second phrase of the retransition (measures 85 to 88) is an exact repetition of the first phrase. Measures 89 to 90 then lead back to F major for the recapitulation:

A literal transcription follows:

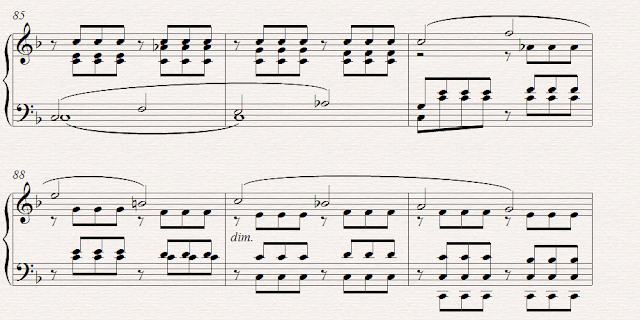

In the string arrangement, Beethoven treats each phrase differently. We discussed measures 81 to 84 last week, but I repeat them here for comparison:

In measure 85, the cello plays the theme an octave lower than in the first phrase. (This answers the first question from last week. The low Cs at the end of measure 84 were preparation for this octave drop.) The viola plays the same notes as before (also an octave lower) but now plays half notes instead of eighth notes. Together, these changes reinforce the feeling of a stretto that Beethoven began in the first phrase. The entrance of the theme in a new octave sounds like a new voice, a fourth statement of the subject. The half notes in the viola sound like a counter subject, and the fact that the half notes begin on beat three rather than beat one reinforces this impression.

The violins play the eighth note accompaniment, but with a twist. Instead of repeated Cs, each triple begins with a B natural, the dominant leading tone. This adds variety to the second phrase, but I think there is a more subtle reason for this change that will become apparent later on. We can now answer the second question from last week. Why did Beethoven not resolve the B natural in the second violin part? He does; he just waits until beat two to resolve it.

In measure 87, we have the final entrance of the subject in the first violin. The second violin joins the viola in playing half notes while the cello takes over the eighth-note accompanimental figure. Having three voices playing half notes and one playing eighth notes (rather than the other way around, as in the piano version) lends the serenity to this passage that a retransition requires. Note the cello omits the B natural in the second triple of each measure, thus avoiding a cross relation in measure 89.

As expected, Beethoven revoices the chords in measures 87 and 88 to avoid the parallel octaves. But why does he give the viola the higher part? Presumably because lower part is the counter-subject, which the viola has already played. In fugal writing, each entrance of the subject or counter-subject is taken up by a new voice. So Beethoven is simply continuing to treat this passage as a stretto.

In measure 89, Beethoven starts the modulation to the home key of F major. Purists will object to calling this a modulation. Technically, going from F minor to F major is a mode shift, not a modulation. But it certainly feels like a modulation. The B-flat in the melody has a definite turning-the-corner-and-heading-back-to-home feel to it. And that, I think, is why Beethoven added all those B naturals to the accompaniment. He wanted B natural ringing in our ears, so the B flat would have this effect.

At the very end of the phrase, Beethoven adds an eighth note C to the melody. Again, he is paying close attention to voice leading. Without that eighth note, we would expect the next note in the first violin to be an F. But, since the next measure starts the recapitulation, it is going be a C. This added eighth note keeps that C from sounding incongruous. In the piano version, the eighth note is unnecessary, because we can hear the return of the opening theme as a new voice rather than as a continuation of this line. (A sensitive pianist would certainly play it that way.)

One last thing to puzzle through is the change in dynamics. In the piano version, Beethoven writes a diminuendo in this passage. In the string version, he drops to pianissimo and crescendos. Why this change? I suspect it is due to what happens next. In the piano version, the recapitulation begins forte. In the string version, it will begin piano (for reasons we will consider next week). Beethoven wants a sudden dynamic shift at the start of the recapitulation. So, if it is going to start piano, he must change the diminuendo in this passage to a crescendo.

In 1801, Beethoven arranged his Piano Sonata No. 9 for string quartet. This blog chronicles my attempt to learn what constitutes good string-quartet writing by examining the decisions Beethoven made in producing this arrangement.

Friday, June 28, 2013

Saturday, June 22, 2013

Movement I - Measures 81 to 84

In measure 81, Beethoven begins the retransition. We have two phrases in F minor, each consisting of a statement and answer of the opening motif:

In the piano version, the second phrase is an exact repetition of the first phrase. In the string version, Beethoven will, of course, not be satisfied with an exact repetition. We will hold off on phrase two until next week. This post will focus on the first phrase.

Here is what a literal transcription would sound like. (Ignore the diagonal lines for now.)

Note there is a voice-leading problem. There are parallel octaves between the first violin and viola going from measure 83 to 84. Mr. Rappaport would never have let me get away with that. But the truth is, even a purist like Mozart did not worry about these things so much in his piano works, provided the parallelism was between the melody and an inner voice and provided the texture was homophonic. What, after all, is the alternative? In an ensemble, you might change the tenor's E to a C, doubling the bass. But you wouldn't hear it as doubling on the piano. It would just sound as if one of the voices dropped out. On the piano, it sounds better to retain the full texture, even with the parallel octaves.

I would not, however, expect Mozart or Beethoven to let this slide in a string quartet, where you hear the voice leading more clearly. So I suspect Beethoven will get rid of the parallel octaves in his arrangement. Here is his solution:

First, Beethoven eliminates the pedal point in measures 81 and 82. This makes sense. The retransition serves to cool things down after the stormy developmental core, so the texture needs to thin out. The pedal point sounds okay on the piano, with its fast decay. But in strings, it would make the texture too heavy. Beethoven also drops the first violin, leaving the second and viola to handle the accompaniment on their own.

In measures 83 and 84, Beethoven makes more radical changes. He reduces he eighth note accompaniment from two voices to one as it is taken over by the cello, and he has the viola double the second violin at the sixth. The first violin finally enters at measure 84 with a third statement of the opening motive. If we hear the viola line as a continuation of the cello line from measures 81 to 82, then the whole phrase takes the form of a fugal stretto.

The amazing thing is Beethoven accomplishes this by simply redistributing the notes in the original version to different voices. As the diagonal lines show, the viola's C-A flat-G-D line comes from moving from the tenor to the alto and back again. The first violin's statement of the theme comes from choosing the C from the bass, then the F from the alto. The only notes from the original that are not redistrubuted are the F and E in the tenor. But these are the precisely the parallel octaves that we wanted to get rid of anyway. Very clever.

Note that Beethoven resolves the first violin and viola lines on the downbeat of measure 85. Why did Beethoven not resolve the second violin line? And why did he drop the cello to a low C on the second half of measure 84? Both of these questions will be answered when we see Beethoven's arrangement of the second phrase next week.

Finally, if you haven't already done so, I invite you to 'like' my professional page at https://www.facebook.com/PhillipMartinComposer. Perhaps you can even listen to a composition or two on the Bandpage tab and decide for yourself whether Beethoven has been able to teach me anything.

In the piano version, the second phrase is an exact repetition of the first phrase. In the string version, Beethoven will, of course, not be satisfied with an exact repetition. We will hold off on phrase two until next week. This post will focus on the first phrase.

Here is what a literal transcription would sound like. (Ignore the diagonal lines for now.)

Note there is a voice-leading problem. There are parallel octaves between the first violin and viola going from measure 83 to 84. Mr. Rappaport would never have let me get away with that. But the truth is, even a purist like Mozart did not worry about these things so much in his piano works, provided the parallelism was between the melody and an inner voice and provided the texture was homophonic. What, after all, is the alternative? In an ensemble, you might change the tenor's E to a C, doubling the bass. But you wouldn't hear it as doubling on the piano. It would just sound as if one of the voices dropped out. On the piano, it sounds better to retain the full texture, even with the parallel octaves.

I would not, however, expect Mozart or Beethoven to let this slide in a string quartet, where you hear the voice leading more clearly. So I suspect Beethoven will get rid of the parallel octaves in his arrangement. Here is his solution:

First, Beethoven eliminates the pedal point in measures 81 and 82. This makes sense. The retransition serves to cool things down after the stormy developmental core, so the texture needs to thin out. The pedal point sounds okay on the piano, with its fast decay. But in strings, it would make the texture too heavy. Beethoven also drops the first violin, leaving the second and viola to handle the accompaniment on their own.

In measures 83 and 84, Beethoven makes more radical changes. He reduces he eighth note accompaniment from two voices to one as it is taken over by the cello, and he has the viola double the second violin at the sixth. The first violin finally enters at measure 84 with a third statement of the opening motive. If we hear the viola line as a continuation of the cello line from measures 81 to 82, then the whole phrase takes the form of a fugal stretto.

The amazing thing is Beethoven accomplishes this by simply redistributing the notes in the original version to different voices. As the diagonal lines show, the viola's C-A flat-G-D line comes from moving from the tenor to the alto and back again. The first violin's statement of the theme comes from choosing the C from the bass, then the F from the alto. The only notes from the original that are not redistrubuted are the F and E in the tenor. But these are the precisely the parallel octaves that we wanted to get rid of anyway. Very clever.

Note that Beethoven resolves the first violin and viola lines on the downbeat of measure 85. Why did Beethoven not resolve the second violin line? And why did he drop the cello to a low C on the second half of measure 84? Both of these questions will be answered when we see Beethoven's arrangement of the second phrase next week.

Finally, if you haven't already done so, I invite you to 'like' my professional page at https://www.facebook.com/PhillipMartinComposer. Perhaps you can even listen to a composition or two on the Bandpage tab and decide for yourself whether Beethoven has been able to teach me anything.

Friday, June 14, 2013

Movement I - Measures 75 to 80

Standard procedure in the development section calls for a pre-core (material of lesser emotional intensity) followed by a core (material that is unstable and dramatic). The core consists of a model that is sequenced in different keys.

Beethoven follows this procedure here. Measures 61 to 64 constituted the pre-core; measure 65 began the core. The model (measures 65 to 70) was first stated in B-flat minor. In measure 75, Beethoven begins a restatement in D-flat major. The restatement is interrupted, however, by a modulation to F minor.

In the piano version, Beethoven has consistently used dynamics to highlight the structure of the core. He continues to follow this procedure here. Measure 77, which begins the modulation, is marked pianissimo, as if to whisper "You didn't expect that, now, did you?"

In the string version, however, Beethoven highlights the structure by modifying the accompaniment. Had he followed by pianistic scheme and patterned the accompaniment here after the original model, we would have this:

Instead, Beethoven gives us this:

Rather than simply repeat the earlier pattern, he has the viola echo the cello's arpeggios, leaving the second violin to manage the tremolos on its own. This interplay raises the intensity of this passage, an effect that is enhanced (as observed last week) by the fact that the arpeggios were eliminated altogether in the bridge between the model statements.

In measure 79, Beethoven does something he has not previously done in the core: give the cello sustained notes, rhythmically doubling the melody. We have heard nothing but eighth notes in the cello for the past 14 measures. So the sustained notes provide a dramatic build-up to the climax on the downbeat of measure 80. After the climax, the cello immediately returns to its eighth note tremolos.

None of this drama is present in the piano version with its relentless arpeggios. At least it is not present in the score.It's up to the performer to discover the harmonic narrative and bring it out in performance. Since the string quartet has a greater expressive range than the piano, there is no need for Beethoven to be so coy.

The final measure illustrates some voice-leading considerations. Adding the long line in the cello in measure 79 required changing the bass in measure 80. The bass is now a D rather than a B-flat. But a second inversion vii/V chord resolving to V does not provide the dramatic half-cadence Beethoven wants. So he flats the D, changing the chord into a German sixth.

Note the way Beethoven resolves the German sixth at the very end of the phrase. Later composers would resolve the viola's A-flat to a G, since the German sixth came to be considered as an exception to the prohibition against parallel fifths. Beethoven, however, still feels the need to avoid the parallel fifths and resolves the A-flat upward to a C. He also meticulously drops the viola's F down an octave before moving to the A-flat. Why? So that he approaches the dissonance (A-flat against the melody's G) in contrary motion. Approaching the dissonance in similar motion (from the high F) would not sound as good. Such Bach-like attention to detail is one of the things that makes Beethoven's music so exceptional.

Beethoven follows this procedure here. Measures 61 to 64 constituted the pre-core; measure 65 began the core. The model (measures 65 to 70) was first stated in B-flat minor. In measure 75, Beethoven begins a restatement in D-flat major. The restatement is interrupted, however, by a modulation to F minor.

In the piano version, Beethoven has consistently used dynamics to highlight the structure of the core. He continues to follow this procedure here. Measure 77, which begins the modulation, is marked pianissimo, as if to whisper "You didn't expect that, now, did you?"

In the string version, however, Beethoven highlights the structure by modifying the accompaniment. Had he followed by pianistic scheme and patterned the accompaniment here after the original model, we would have this:

Instead, Beethoven gives us this:

Rather than simply repeat the earlier pattern, he has the viola echo the cello's arpeggios, leaving the second violin to manage the tremolos on its own. This interplay raises the intensity of this passage, an effect that is enhanced (as observed last week) by the fact that the arpeggios were eliminated altogether in the bridge between the model statements.

In measure 79, Beethoven does something he has not previously done in the core: give the cello sustained notes, rhythmically doubling the melody. We have heard nothing but eighth notes in the cello for the past 14 measures. So the sustained notes provide a dramatic build-up to the climax on the downbeat of measure 80. After the climax, the cello immediately returns to its eighth note tremolos.

None of this drama is present in the piano version with its relentless arpeggios. At least it is not present in the score.It's up to the performer to discover the harmonic narrative and bring it out in performance. Since the string quartet has a greater expressive range than the piano, there is no need for Beethoven to be so coy.

The final measure illustrates some voice-leading considerations. Adding the long line in the cello in measure 79 required changing the bass in measure 80. The bass is now a D rather than a B-flat. But a second inversion vii/V chord resolving to V does not provide the dramatic half-cadence Beethoven wants. So he flats the D, changing the chord into a German sixth.

Note the way Beethoven resolves the German sixth at the very end of the phrase. Later composers would resolve the viola's A-flat to a G, since the German sixth came to be considered as an exception to the prohibition against parallel fifths. Beethoven, however, still feels the need to avoid the parallel fifths and resolves the A-flat upward to a C. He also meticulously drops the viola's F down an octave before moving to the A-flat. Why? So that he approaches the dissonance (A-flat against the melody's G) in contrary motion. Approaching the dissonance in similar motion (from the high F) would not sound as good. Such Bach-like attention to detail is one of the things that makes Beethoven's music so exceptional.

Saturday, June 8, 2013

Movement I - Measures 71 to 74

Visually, measures 71 to 74 look similar to the preceding six measures.

There are, however, several differences:

(1) The harmonic motion speeds up. Previously, the harmony changed every two measures. Now it changes every measure.

(2) The previous passage, in B-flat minor, was harmonically static.This passage modulates, reaching D-flat major on the downbeat of measure 75.

(3) The melody is transformed. In the previous passage, we heard the same melody three times. In measures 71 to 72 that melody is (roughly) inverted. And in measure 74 it is interrupted and replaced with a new syncopated figure.

In the piano version, Beethoven retains the same accompanying figure in these measures that he used in the previous measures. The only clue the accompaniment offers that something different is going on is the octave drop in measure 74, which, along with the new syncopated melody, dramatizes the arrival in D-flat major.

In the string version, however, Beethoven helps us hear the newness of this material by changing the accompaniment. Had he followed the same pattern as in the previous section, we would have this:

Because the harmony now changes every measure instead of every two measures, this scheme doesn't work well. It sounds strange to arpeggiate the harmonies in the odd measures but not the even measures. Beethoven might have added arpeggios to the even measures as well. But he preferred to dial things back instead. He drops the arpeggios altogether and has the cello join the middle strings in their tremolo. (As we shall see next week, dialing things back now gives him the chance ratchet things up more effectively later on. This is a technique known to all good composers and horror film directors.)

Even though the cello joins in the tremolo, it retains its individuality by playing eighth notes to the middle strings' sixteenth notes. It also employs the device Beethoven has used previously to accentuate the downbeat: an octave dip on the first note of each tremolo.

Note Beethoven changes the point where the bass drops down an octave to the low A-flat. In the piano version, this happens at the beginning of measure 74. In the string version, it happens three beats earlier. Why? Presumably, it is because the very climax of the passage has changed. In the piano version, the climax is on the sforzando in measure 74. In the string version, Beethoven eliminates this sforzando and marks a forte at the beginning of measure 73, shifting the climax to this point. In addition, he lands emphatically on the final cadence, specifying a forte-piano on the downbeat of measure 75. In the piano version, this measure is marked piano, so as not to upstage the sforzando of the previous measure. (These quarter notes aren't in the real score, by the way. I added them to avoid ending the sound sample on an unresolved dominant.)

What are these changes all about? Beethoven is being sensitive to the realities of string writing. A pianist can land forcefully and effectively on that high G-flat. But this would not work in strings. The violin's sound is too thin in that register to produce a convincing sforzando with no assistance from the accompaniment. The downbeat of measure 72, assisted by the change of harmony and a low A-flat in the cello, is a more natural place for the climax.

This is the kind of change an arranger might be afraid to make. How can you move the climax of the phrase? Isn't that tampering too much with the original? But Beethoven, who doesn't have to worry about offending himself, has no qualms about making whatever changes the new medium requires. Fidelity to the original is desirable. But it's more important that the music sound good.

(1) The harmonic motion speeds up. Previously, the harmony changed every two measures. Now it changes every measure.

(2) The previous passage, in B-flat minor, was harmonically static.This passage modulates, reaching D-flat major on the downbeat of measure 75.

(3) The melody is transformed. In the previous passage, we heard the same melody three times. In measures 71 to 72 that melody is (roughly) inverted. And in measure 74 it is interrupted and replaced with a new syncopated figure.

In the piano version, Beethoven retains the same accompanying figure in these measures that he used in the previous measures. The only clue the accompaniment offers that something different is going on is the octave drop in measure 74, which, along with the new syncopated melody, dramatizes the arrival in D-flat major.

In the string version, however, Beethoven helps us hear the newness of this material by changing the accompaniment. Had he followed the same pattern as in the previous section, we would have this:

Because the harmony now changes every measure instead of every two measures, this scheme doesn't work well. It sounds strange to arpeggiate the harmonies in the odd measures but not the even measures. Beethoven might have added arpeggios to the even measures as well. But he preferred to dial things back instead. He drops the arpeggios altogether and has the cello join the middle strings in their tremolo. (As we shall see next week, dialing things back now gives him the chance ratchet things up more effectively later on. This is a technique known to all good composers and horror film directors.)

Even though the cello joins in the tremolo, it retains its individuality by playing eighth notes to the middle strings' sixteenth notes. It also employs the device Beethoven has used previously to accentuate the downbeat: an octave dip on the first note of each tremolo.

Note Beethoven changes the point where the bass drops down an octave to the low A-flat. In the piano version, this happens at the beginning of measure 74. In the string version, it happens three beats earlier. Why? Presumably, it is because the very climax of the passage has changed. In the piano version, the climax is on the sforzando in measure 74. In the string version, Beethoven eliminates this sforzando and marks a forte at the beginning of measure 73, shifting the climax to this point. In addition, he lands emphatically on the final cadence, specifying a forte-piano on the downbeat of measure 75. In the piano version, this measure is marked piano, so as not to upstage the sforzando of the previous measure. (These quarter notes aren't in the real score, by the way. I added them to avoid ending the sound sample on an unresolved dominant.)

What are these changes all about? Beethoven is being sensitive to the realities of string writing. A pianist can land forcefully and effectively on that high G-flat. But this would not work in strings. The violin's sound is too thin in that register to produce a convincing sforzando with no assistance from the accompaniment. The downbeat of measure 72, assisted by the change of harmony and a low A-flat in the cello, is a more natural place for the climax.

This is the kind of change an arranger might be afraid to make. How can you move the climax of the phrase? Isn't that tampering too much with the original? But Beethoven, who doesn't have to worry about offending himself, has no qualms about making whatever changes the new medium requires. Fidelity to the original is desirable. But it's more important that the music sound good.

Saturday, June 1, 2013

Movement I - Measures 65 to 70

As I mentioned in the last post, this passage is particularly pianistic:

A literal transcription is virtually impossible at this speed, so I changed the arpeggios to something more string-friendly:

Beethoven does something quite different in his arrangement. Instead of arpeggios, he uses sixteenth-note tremolos in the middle strings. To keep this from getting boring, he adds a new countermelody in the cello. This countermelody takes up the arpeggio idea from the piano version, but the arpeggios are now staccato eighth notes and span two octaves. The countermelody provides the motion when the melody has a long note but then drops out on each even measure when the melody is moving. This scheme results in a cleaner, less busy sound.

Beethoven also changes the dynamics. The piano score contains a crescendo in the last two measures. (A short-lived crescendo. The very next measure, measure 71, will be marked piano.) Beethoven drops the crescendo in the string score and adds a forte-piano to the first beat of each odd measure. The forte-pianos add to the excitement, and it is the tremolos that makes them possible. Forte-pianos would sound very strange in the piano version.

Beethoven begins this passage with a dramatic leap in the second violin, which helps to differentiate this new section. Beethoven went out of his way to make this leap a large one. We noted last week that he gratuitously widened the spread between the second violin and viola at the end of measure 64. This widening sets up the high D-flat in measure 65. A more natural voice-leading would have had the violin leaping, less dramatically, from a B-flat.

Why does Beethoven invert the voicing in the tremolo chord, giving the second violin the B-flat and the viola the D-flat? Perhaps one reason is to make the leap in the second violin that much larger. But I suspect the main reason is he simply didn't want the viola to play the same note on the downbeat as the in rest of the measure. He did something similar in the first measure of the piece, scoring it as

rather than

This movement, in each case, ensures that we hear the chord on the downbeat as an entity distinct from the ensuing tremolos.

A literal transcription is virtually impossible at this speed, so I changed the arpeggios to something more string-friendly:

Beethoven does something quite different in his arrangement. Instead of arpeggios, he uses sixteenth-note tremolos in the middle strings. To keep this from getting boring, he adds a new countermelody in the cello. This countermelody takes up the arpeggio idea from the piano version, but the arpeggios are now staccato eighth notes and span two octaves. The countermelody provides the motion when the melody has a long note but then drops out on each even measure when the melody is moving. This scheme results in a cleaner, less busy sound.

Beethoven also changes the dynamics. The piano score contains a crescendo in the last two measures. (A short-lived crescendo. The very next measure, measure 71, will be marked piano.) Beethoven drops the crescendo in the string score and adds a forte-piano to the first beat of each odd measure. The forte-pianos add to the excitement, and it is the tremolos that makes them possible. Forte-pianos would sound very strange in the piano version.

Beethoven begins this passage with a dramatic leap in the second violin, which helps to differentiate this new section. Beethoven went out of his way to make this leap a large one. We noted last week that he gratuitously widened the spread between the second violin and viola at the end of measure 64. This widening sets up the high D-flat in measure 65. A more natural voice-leading would have had the violin leaping, less dramatically, from a B-flat.

Why does Beethoven invert the voicing in the tremolo chord, giving the second violin the B-flat and the viola the D-flat? Perhaps one reason is to make the leap in the second violin that much larger. But I suspect the main reason is he simply didn't want the viola to play the same note on the downbeat as the in rest of the measure. He did something similar in the first measure of the piece, scoring it as

rather than

This movement, in each case, ensures that we hear the chord on the downbeat as an entity distinct from the ensuing tremolos.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)